How to alleviate or, better yet, avoid an encounter with poison ivy

From the March-April 2014 issue of Scouting magazine

Emergency Situation: You’re day hiking with your troop when suddenly you get the almost irresistible urge to scratch at your ankles. Looking down for the offending swarm of mosquitoes, you notice not a red bug bite but rather the beginnings of a nasty, bumpy rash — you suspect it could be from poison ivy.

What should you do?

Solution: Don’t scratch! Admittedly, that’s more advice than solution. But it still holds. Scratching can not only spread the offending agent (urushiol, which is actually a resin, not an oil) that causes contact dermatitis (better known as an irritating rash), but it can also lead to infection.

We’re all familiar with the age-old saying, “Leaves of three, let them be.” This is fine as far as it goes, though poison sumac — equally, if not more, itch-inducing than poison ivy — defies the three-leaf description. It might have many leaves, and it might come in shrub or tree form. But even identifying poison ivy can be tricky. Depending on the season, poison ivy leaf clusters might be green, yellow, orange or red. And as its name implies, it might appear as a vine.

Typically, at least 50 percent of people who come into contact with poison ivy will develop some form of rash within a few hours or days of exposure. (Some people are less sensitive than others, but scientists have yet to figure out how the lucky half got so lucky.) In most cases, the itching symptoms of the rash can be treated in the field with a cold compress or by running cool water over affected areas.

While the rash might blister, note a common misconception: The fluid in the blisters cannot spread the rash. That said, urushiol on the skin is easily transferrable via hands or clothing. Wash your hands and all affected clothing.

But what about when you’re out in the field? Here, a few remedies can reduce discomfort, though only one is said to reduce or eliminate the rash.

One option, besides simple soap and water, is an over-the-counter product called Tecnu, which claims to be more effective than ordinary soap at removing urushiol from the skin if applied right after exposure. (Tecnu was invented in the 1960s as a waterless cleanser for removing radioactive dust from skin and clothing … if that makes you feel any better about a harmless rash.) Add it to your first-aid kit for in-the-field treatment.

The gel-like interior of the aloe plant can cool and soothe your rash. Other natural itching remedies include witch hazel and tea tree oil, either of which would be appropriate to pack in an outdoor emergency kit. Calamine lotion has been used for decades to treat contact dermatitis, and it still works to reduce itching. In severe cases, prescription cortisone cream might also be used.

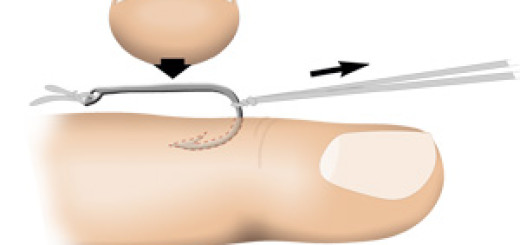

Ultimately, another old saying holds true: “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” You can avoid exposure by wearing hiking boots and long socks, or pants, and wearing gloves when you remove them.

Or hike in the dead of winter.

This was a great article. It’s always better to be prepared and know what to expect in the event that we run into this situation.